The HIV Care System Is Breaking Before Congress Even Cuts It

Administrative sabotage has already destabilized HIV services nationwide. Actual funding cuts would finish the job.

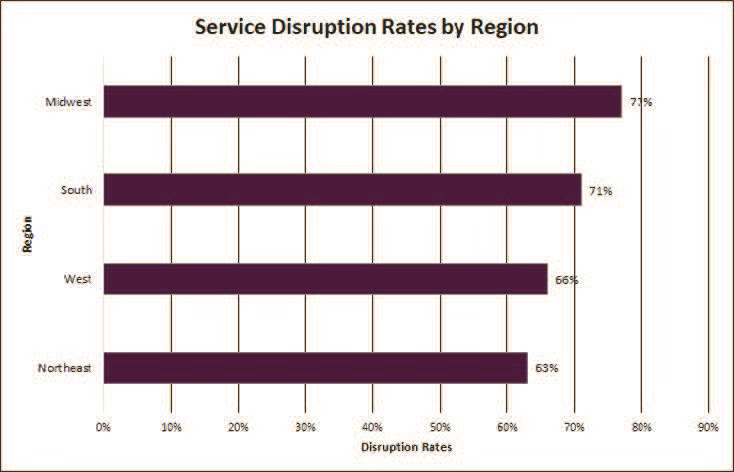

In October 2025, the Emergency HIV Clinical Response Task Force surveyed 526 HIV clinicians across the United States. Seventy percent reported service disruptions affecting their patients, with the Midwest and South hit hardest at 77% and 71%. Gender-affirming care topped the list of disrupted services at 33%, followed by housing support at 26% and PrEP or PEP access at 25%. Transgender people and immigrants bore the heaviest impact, with 41% and 38% of clinicians reporting these populations were most affected.

These numbers tell an important story, but not the one many headlines suggest. The disruptions in this survey are not the result of Congressional budget cuts to HIV programs. No legislation has eliminated Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program funding or CDC prevention dollars. Instead, they stem from administrative actions, grant recissions, and bureaucratic obstruction that destabilized HIV services months before Congress debated any cuts at all.

That distinction matters. It reveals how vulnerable the HIV care infrastructure has become, and how much worse things could get if proposed eliminations of HIV programs and broader healthcare funding cuts move forward.

The Administrative Stranglehold

The current disruptions trace directly to Office of Management and Budget Director Russell Vought’s systematic manipulation of the federal budget process. Before joining the Trump administration, Vought outlined these tactics in Project 2025, describing how “apportioned funding” could “ensure consistency with the President’s agenda.” He has executed this strategy with precision.

Rather than releasing appropriated funds to agencies like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in standard apportionments, Vought shifted to monthly releases requiring Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) review for every grant award. By August 2025, the CDC’s center for HIV and tuberculosis prevention had spent $167 million less than historical averages, the Ryan White Program underspent by $105 million, and mental health funds at the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration lagged by more than $860 million.

The money exists. Congress appropriated it. Administrative roadblocks are what prevent it from reaching clinics, health departments, and community organizations.

The human cost is visible in provider reports. When funding delays hit in July 2025, 81 HIV organizations wrote to HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. warning that “with every day of delayed FY2025 funding release, the delivery of essential HIV services is compromised.” Clinics laid off case managers, reduced clinician hours, closed sites, and scaled back hotlines. The funds eventually arrived about a month later, but the damage—to staff capacity, patient trust, and continuity of care—was done.

At St. John AIDS outreach ministry in New Orleans, program director Tamachia Davenport faced a choice: cut staff or cut supplies when CDC funds did not arrive on time. To keep staff from fleeing to more stable jobs, she stopped buying condoms the organization distributes to prevent sexually transmitted infections—despite Louisiana’s already high rates of HIV, chlamydia, and gonorrhea, and the fact that condoms cost far less than treating any of them.

One CDC official summarized the view from inside: “Everyone’s inbox is full of letters from grant recipients asking, ‘How do we proceed?’ We just say, ‘Please wait.’”

Robert Gordon, a public policy specialist at Georgetown University and former assistant finance secretary at HHS, described the strategy plainly: “This is a sophisticated strategy to cause money to lapse and then say, ‘If they can’t spend it, they don’t need it.’”

The Unlegislated Threat

While administrative actions create the current disruptions, proposed legislation in Congress represents a qualitatively different threat.

In September 2025, the House Appropriations Committee released its FY2026 funding bill eliminating all CDC HIV prevention funding—approximately $1 billion—and cutting the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program by $525 million, or 20%.

The bill does not merely trim budgets. It eliminates program components entirely. Ryan White Part F, including AIDS Education and Training Centers, the Dental Reimbursement Program, and the Minority AIDS Initiative, would disappear. The $220 million for the Ending the HIV Epidemic initiative would be eliminated. Direct grants to more than 400 HIV clinics providing care and treatment through Ryan White Parts C and D would end.

Carl Schmid, executive director of the HIV+Hepatitis Policy Institute, summed up the stakes: “This is not a bill for making America healthy again, but a disastrous bill that will reignite HIV in the United States.”

The Senate tells a different story. In July 2025, the Senate Appropriations Committee advanced a bipartisan bill that maintains flat funding for all parts of the Ryan White Program ($2.57 billion), level funding at $220 million for Ending the HIV Epidemic, and flat funding for CDC HIV prevention. The contrast could not be clearer.

Researchers at Johns Hopkins Medicine modeled what would happen if federal funding for Ryan White ended. Their study in the Annals of Internal Medicine projects 75,436 additional HIV infections through 2030, a 49% increase. As senior author Dr. Todd Fojo noted, effective treatment is the most powerful form of HIV prevention.

No final FY2026 budget has been enacted. The government is operating under a continuing resolution, and the gap between House and Senate proposals is unresolved. But the threat is not hypothetical, and the clinician survey’s forward-looking data reflects it: 72% anticipate moderate or significant service disruptions in the next 6–12 months, rising to 77% for the following 12–18 months.

The Broader Ecosystem Under Siege

The clinician survey captures disruptions to direct HIV services, but not the compounding pressures from Medicaid restructuring that threaten both coverage for people living with HIV and the financial stability of AIDS service organizations.

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act, signed July 4, 2025, reduces Medicaid expansion eligibility from 138% to 100% of the federal poverty level, affecting an estimated 200,000 people with HIV. This is not a marginal tweak: 40% of non-elderly adults with HIV rely on Medicaid, nearly three times the rate of the general population. Starting in 2027, expansion adults ages 19–64 must complete 80 hours per month of approved activities to maintain coverage, and semi-annual eligibility redeterminations will replace annual reviews, injecting churn into programs where uninterrupted access to antiretroviral therapy is a clinical requirement, not a luxury.

Many AIDS service organizations converted to Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) status after the Affordable Care Act to serve newly insured patients and stabilize revenue. Medicaid comprises 43% of FQHC revenue. The OBBBA cuts into this income through provider tax caps that ratchet down over time and by capping state-directed payments at 100% of Medicare rates in expansion states. At the same time, the Congressional Budget Office projects 7.8 million people will lose Medicaid coverage overall. Enhanced ACA premium tax credits expire at the end of 2025, and so far Congress has not extended them.

As Davenport of St. John AIDS outreach told KFF Health News, “A lot of us are having to rob Peter to pay Paul.” But what happens when Peter gets defunded? Maybe the “Good Christians” in the halls of Congress can tell us.

Ground Truth: What’s Happening Now

Local decisions layered on top of federal obstruction are already shutting people out of care.

In Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, the public health department laid off six workers, including half its disease investigators, when HIV prevention and surveillance grants expired at the end of May with no information about future funding. The grants were restored a month later, but only half the positions were refilled. “So now we’re behind, and cases are still being reported every day that have to be investigated,” said director Raynard Washington.

In Dallas County, Texas, public health director Philip Huang waits for nearly 30% of the promised award for emergency preparedness with no timeline or clarity, making basic staffing decisions feel like a gamble.

Breanne Armbrust, executive director of Richmond’s Neighborhood Resource Center, summed up the cumulative burden on patients: “They’re already sick or in need of care and asking them to do one more thing when their acuity levels might be high is too much, and it’s unreasonable.”

The Warning We Cannot Ignore

The clinician survey documents disruptions caused by administrative obstruction at a time when HIV programs still technically have appropriated funding. It is a snapshot of a system that is already unstable.

If the House FY2026 proposal eliminating CDC prevention funding and cutting Ryan White by $525 million becomes law, these disruptions will not simply “increase,” they will scale into system failure. Each new HIV infection carries an estimated $501,000 in lifetime healthcare costs. The Ryan White Program in 2023 achieved a 90.6% viral suppression rate among 576,000 clients. These programs work. Dismantling them would reverse decades of progress in a matter of years.

The workforce crisis compounds the threat. The United States needs 1,500 additional HIV specialists to reach 90-90-90 benchmarks. The South already has only 8 providers per 1,000 people with HIV, compared with 11 nationally. Counties that have reached at least one 90-90-90 target have 13 providers per 1,000. Eliminating AIDS Education and Training Centers, as the House bill proposes, would deepen that shortage just as demand for services intensifies.

None of this is theoretical. Administrative sabotage is already cutting off care people depend on to stay healthy, alive, and connected to treatment. Layer a legislative funding strike on top of a system this fragile, and the outcome is entirely predictable: preventable infections, preventable deaths, and preventable suffering concentrated among people already pushed to the margins.

Policymakers do not need another awareness campaign to understand the stakes. They need to treat these proposals for what they are, a slow-motion dismantling of the HIV care infrastructure that has held the epidemic in check. The choice in front of them could not be more plain: reinforce that infrastructure, or stand in history as merchants of death.